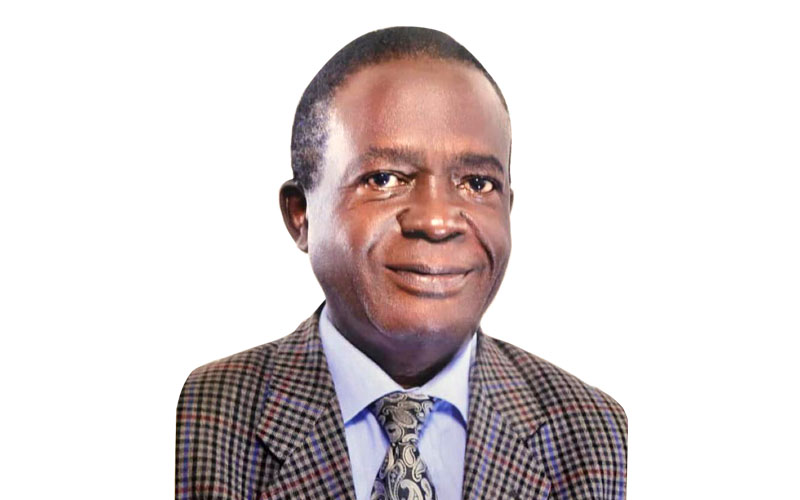

Any life can fall into two chapters: Part I and Part II. I shall here write about a certain part of the life of the Late Dr Aggrey Kiyingi, the deceased world renown cardiologist and for long a friend.

I cant locate exactly when we first met, but there is a bit of important history here leading us to what bloomed into a mutual friendship. The history of Uganda, like all, has had its fair share of tragedies. In May 1966 a cabinet Minister, Balak Kirya, together with his four colleagues were suspected of plotting to overthrow Prime Minister Milton Obote. Early one morning without warning all were hauled from a Cabinet meeting board room at Entebbe State House. Kirya, along with Grace Ibingira, Mathais Ngobi, George Magezi and Dr Emmanuel Lumu, would serve five consecutive years while held in Luzira Maximum Security prison. They saw the sun only after the new President Idi Amin released over 50 political detainees, following his astonishing 1971 coup.

After his release Kirya settled down into a quiet life. However he was yanked out of his early retirement from public life when his old tormentor, Obote, returned to power in 1980. Fearing he would be thrown back into the cooler, he fled into neighbouring Kenya. There he joined the nascent rebel movement fighting to overthrow the Obote regime. But one day there was a sudden swoop of the rebels which picked up as many, Balak Kirya, being a prize trophy.

Back to his old address, alone in a cell, Kirya had a lot to reflect on his life. One day, he surrendered his life to Jesus Christ as a personal Lord and Savior. When the Obote regime fell and Kirya saw the light of day he was a changed man. There was a promise he had made to God that if he ever came out alive he would use the rest of his time here on earth by reaching out to leaders with the Gospel of Christ. So when President Museveni appointed him Minister of State in the Office of President, Kirya now used that as a launching pad to start the Prayer Breakfast Ministry targetting leaders.

In 1997 I was introduced to this ministry by Hon Captain Gad Gasatura, a former member of the Constituent Assembly, while on a vsit to Chicago, US, where I was based. Upon return to Uganda I was invited to attend the regular reach out breakfast fellowships held at Fairway Hotel. By then the founder, Balak Kirya, had passed on. But there in the midst sat his widow Grace. I never left.

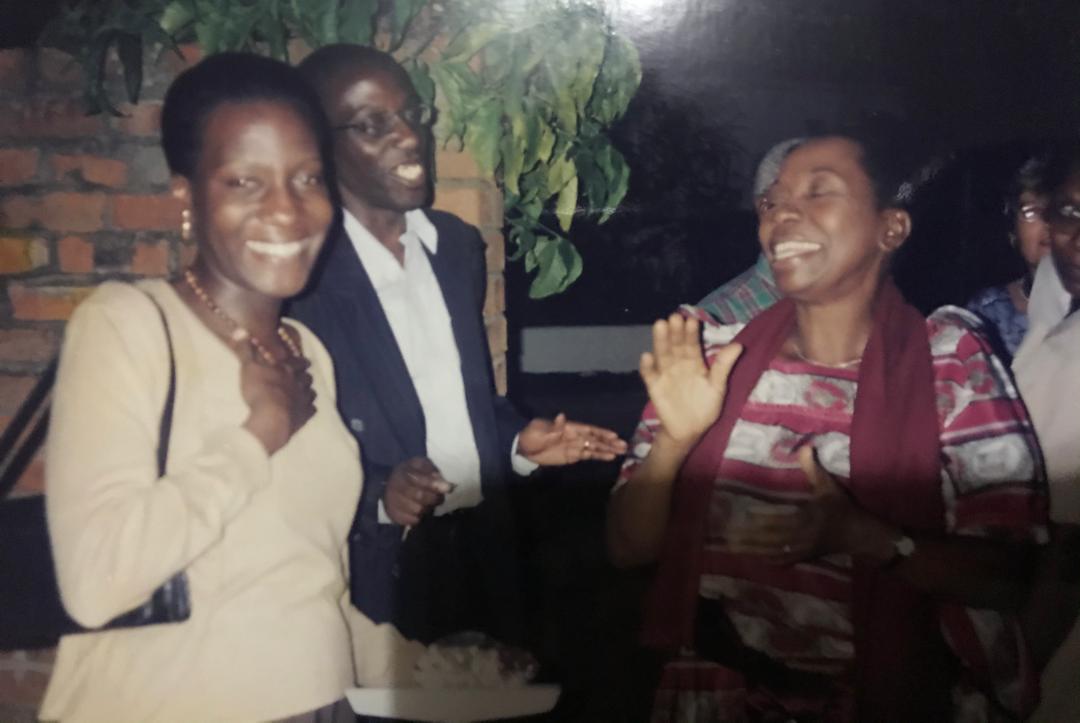

There I also met a lawyer going by Robinah Kiyingi, with whom we became fast friends. I noticed though she often came alone. But one day I found her sitting next to a gentleman dressed in a snowhite white suit. He had such a calm countenance around him, disarming and welcoming. I needn’t guess much. His name was Dr Aggrey Kiyingi.

Born to Azaliya Ssebowa, in 1955, Aggrey was a gifted boy, perhaps a prodigy. The Ssebowas believed in the power of education to change lives. Perhaps it is worthy pausing here to first explain why he was named Aggrey.

In the late 1920s the British Colonial government started to express interest in managing education in Uganda, hitherto run by missionaries. To inform policy they put up the Phelps-Stokes Commission which went about soliciting views. Among the Commisioners was an eminent Ghanain educator, Dr. James Emmanuel Kwegyir Aggrey, already an accomplished educator, Pan-Africanist, and public intellectual. When the commissioners visited King’s College Budo, students were amazed to see a black African ( these were the 1930s) who could stride so easily as an equal of the white man. Dr Aggrey left such a huge impression on those lads that soon after excited students would strike to demand equal rights with whites. When the school authorities expelled them these nationalist Budo students, among whom was Ignatius Musazi and Polycarp Kakoza, all who would leave a mark on Uganda, went on to found Aggrey Memorial School, in Bunamwaya, still flourishing to this day.

The young Aggrey was hurried to Budo Junior School. As one of his classmstes once told me, “Aggrey was one of the brightest in his class. He could quickly solve any problem before any of us!” A star student from there he moved on to King’s College Budo, where he resided in Nigeria House.

Besides academics, Aggrey had also a love for music. Anyone familiar with Budo then had to know the famous Nightingale singers, famous for their captivating ballads, and soon Aggrey became a jovial choralist. The Nightingales would also occasionally link up with their singing counter parts at Gayaza High School. On one of those enconters Aggrey’s eye fell on a beautiful belle called Robinah Kayaga.

Although it was their mutual love of music that drew them to each other, there was also another motivating aspect. Robinah had been raised in Kitetika, Gayaza road, only a few miles away from Busukuma, where Kiyingi family home was. They were both exceptionally bright students too. In 1972 Aggrey was admitted to Makerere University for Medical School while Robinah joined Law School.

Another thing pulling them together was because Aggrey and Robinah were not only both children from the traditional Anglican church but at a certain point earlier on had also accepted Jesus as a personal savior. In local speak they were “balokole”! While this must have given Aggrey an edge over the hotly pursued Robinah, as she was a striking beauty, winning her was never going to be easy.

All those who knew Aggrey can confess that besides his brilliance, he was one man who once he was determined to achieve anything, no dam – high or low- could stand in his way! Capturing the beautiful Robinah was perhaps the toughest test of his life then but typical of him he left nothing to chance. Those who saw his courtship recall Aggrey even pulling in the support of Namirembe heavy weights clergy to weigh in on her and accept this promising young man. After a spirited courtship Robinah alas yielded and they tied the knot, at Namirembe Cathedral, just before he graduated.

Perhaps because he was much apprehensive of his rivals, or, it was a secretive nature of his, Aggrey did not even alert his classmates, most of whom got to know of the wedding the day after. “I couldn’t believe someone I had been with together at school for so long,” one of his old classmates shared with me years later, “could marry without inviting any of us!” But that was Aggrey.

By 1977, when Aggrey graduated, medical doctors who had once been the most prized profession given their scarcity and rare expertise in Uganda, had lost vogue. The brutal years of Amin’s bungling dictatorship had pushed virtually all professinals out of the country, in search of greener pastures. And so it were that soon after graduation, this young couple, fled to neighbouring Kenya to scour a decent living.

In Kenya Aggrey started out at a village hospital in Kitui, Machakos and later moved to Kalolemi hospital in Mombasa. Life was not easy for the young couple and at one point they shared home with Robinah’s sister, Dr Eve Kasirye Alemu, a chemist who had also moved there. Always his eyes on bigger goals Aggrey secured a scholarship that enabled him move to Australia.

Once in Australia Aggrey took on specialist cardiology training in Sydney, at Westmead and Concord Hospitals. By the time we met he had excelled and was one of the most respected cardiologists globally with him advising over a dozen pharmaceutical companies involved in heart research medicine. His practice in Australia had soured enabling them reap great wealth, and of which he was eager to share with his country.

Here there is an aspect we need highlight about the Kiyingis. Successful Ugandans straddling in the diaspora tend to fall into two classes. There are those scarred by the memory of their harsh upbringing who vow never to return home except for those “quickie- return forced visit” to bury their parents, like some favor or, some, who just pass by to vainly pose off their global wares. Another class is one which for all the tribulations of their homeland never loose a love for the motherland, occasionally visiting and endeavoring to give back as much. Aggrey was clearly in the latter category.

In the early 2000s every now and then he would hit the headlines for his philantropic work- donating billions of shillings to pet projects. Once it was millions to his Buziga local church where he sponsored a music CD by the church choir of which he was a patron. Aggrey was fascinated with computers and he set up a computer company, Dehezi International, to promote ICT in Uganda. This company made it a habit to donate computers to the Kingdom of Buganda, which he cherished. But his most prized dream was putting up what he dreamed to be the best heart hospital in East Africa, around old Kampala, a project where he sunk billions of shillings.

Although Aggrey had a punishing schedule each time he would drop in town he would make it to our prayer breakfast fellowships. I always looked forward to these visits as occasionally after the meeting we would linger behind to catch up. I was also endeared to him because his younger brother, Dr Stephen Mayombwe, had been not just a schoolmate at Budo but a best friend. Once we walked from Fairway Hotel down to his office on Impala Avenue sharing lighly on a number of subjects. Midway he paused and he mentioned something memorable, “Always walk as much as you can, for it’s good for your heart!” I would never forget that lesson coming from a world renowned heart surgeon.

As our friendship bloomed Aggrey and Robinah would now and then invite me over to their palatial home rising up in Buziga. They were both totally committed to Uganda. In the 1980s Aggrey had lost his father who was gunned down during the liberation struggle. That did not deter this young family already successful overseas from returning home. Once stability returned they set up a beautiful mansion up on the hill looking down on Kampala. I remember once during a dinner there, the late General Elly Tumwine, teasing Aggrey, “this must bring you more fulfillment than all the honors you might have received back in Australia!” He beamed.

In the course they introduced me to their children. The eldest Samalie was pursuing a double law and business degree in Australia, and whenever around, would come for our fellowships along with Robinah. She was vibrant and there was no doubt she would go far. Kibuka was in Medical School in Australia, following Dad’s path. Kirabo was at Budo, soon to join Medical School, after excelling. Sanyu, the youngest, was secure in a Kampala school. At one event in their home Samalie spoke glowingly on behalf of her siblings and praised them for always pushing them to aspire for excellence in life. “Our parents would never give us anything less than the best!”

Yet it is Robinah whom I would get to know better and she became much more than a sister. She was a prayer partner and confidant. I recall once visiting her down in her law offices which were overlooking the old Kampala taxi park. “Why would you have offices over in this crowded place,” I teased her as I sniffed around. “But Martin you are such a snob!” she rubbed me off with a down to earth snippet. “This is where the business is”! When we had our first child Robinah quickly drove through a stormy weather and left with us a beautiful message, a moment ever to treasure.

Somewhere along, like a bolt from the blue, one day I heard all was not well in the Kiyingi steady as a rock relationship, or so I thought. I struggled to put it all together but there I stood in a trance. The macabre events thereafter leading to the murder of my friend Robinah and the subsequent arrest of Aggrey on murder charges will remain like a blur.

I last saw Aggrey during the funeral service of Robinah where he gave an incoherent speech. After his acquittal he took on a life totally different from the man I had earlier known. In fact sometimes I could not recognize him anymore. When a few weeks ago I learnt he had passed away almost without warning my mind went back to the good old days. Here was a young couple immensely blessed who had decided to partially relocate to Uganda where their lives drew inspiration on the many who looked up to them. But the devil has such a long and ugly hand. All I could do was pray, what else; thankful for the memory of a once beautiful and shining couple! May Robinah and Aggrey RIP!

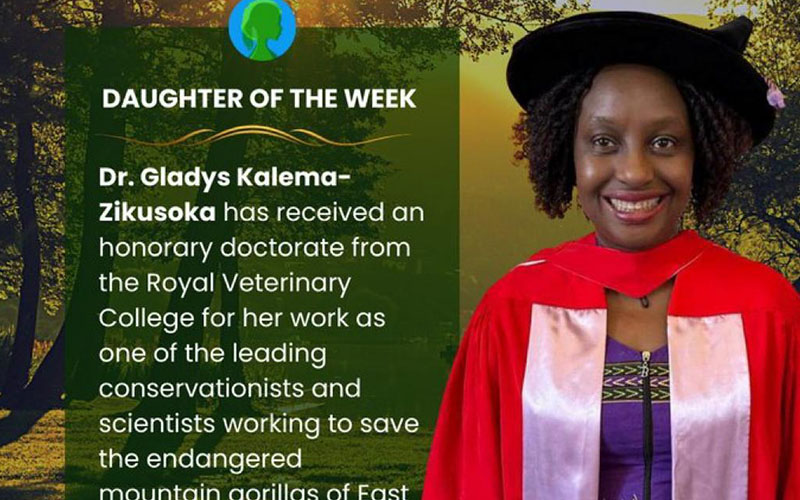

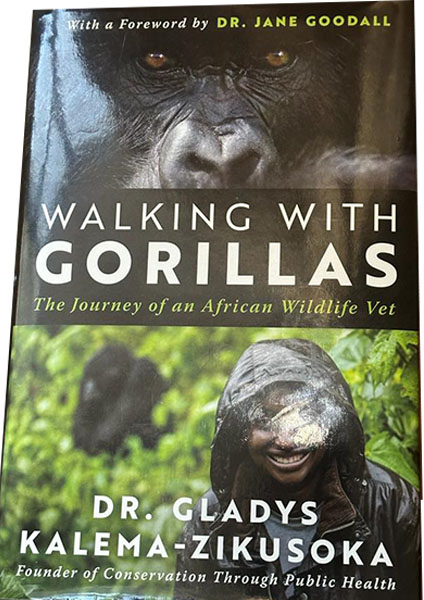

I must say I found this life of hers curious. Yes I had grown up with a guard dog at home- we called him Snap; but a life dedicated to taking care of wildlife was just out of my depth. If anything all I knew based on my university days was students who got to study vet medicine it was because they had missed out on their first choice- human medicine. But here was someone for whom practicing vet medicine by scouring national parks, habitat for wildlife, trekking to treat mountain gorillas, among others, was a life passion.

I must say I found this life of hers curious. Yes I had grown up with a guard dog at home- we called him Snap; but a life dedicated to taking care of wildlife was just out of my depth. If anything all I knew based on my university days was students who got to study vet medicine it was because they had missed out on their first choice- human medicine. But here was someone for whom practicing vet medicine by scouring national parks, habitat for wildlife, trekking to treat mountain gorillas, among others, was a life passion.