In his mind Suubi always dreamt that after school, once he got a good job, married a beautiful girl, all would be well. The hard life he had endured while growing up would all come to an end.

Suubi had narrowly survived the harsh guerrilla war that brought the new military government in power. It had all come at such a huge personal cost. Suubi had lost both his parents, grannies and four siblings. Fate befell him when the family home was bombed after some neighbour alleged they had been sheltering guerrillas. Suubi had not been home at the time of attack, for he was down at the well, but when he got back he found once his home all leveled, with dismembered bodies, everywhere, of people he loved.

He fled. For days and nights, surviving on cassava he stole from gardens and drinking water from stagnant wells, he eluded government soldiers searching for rebels, as he made his way through the bush to the city. When he got to the city it was now a question who would take him up. He saw lots of kids milling around the streets and he considered starting life there too. But then he recalled he had an Uncle, Nkalyanzekka, a younger brother of his murdered Dad, who was a big shot in the city.

But he hesitated going there. Suubi knew that Uncle Nkalyanzekka had long cut himself from his family, which he despised. He had last seen him almost a decade ago when he came for a funeral of an aunt, in a big car, and quickly left once the funeral was over.

“That brother of mine is a very proud man,” Suubi had often heard his father complain. “He forgets he went to school only because we sacrificed and let all the school fees be used for him. But since he got up he thinks we are too small for him.”

That was part of the truth. Having got up in society Mr Nkalyanzekka had formed all sorts of negative views about the relatives he had left behind. He chided them for not being developmental like him. “Look,” he would hiss back in his palatial home of five bedrooms, “those people are so lazy. With all that land they still ask me money. All they do is drink and spend all their earnings in witchcraft chasing fantasies.”

So, how could he now go to Uncle Nkalyanzekka and ask for shelter when he had this low opinion of his family. But then he had no choice. Indeed, once he got to the house, tucked in a leafy suburb, before even greeting him, Uncle Nkalyanzekka on realizing who he was, cried through the window, “What has brought you here, boy, all rumpled up like this!”

“Everyone in the village was killed,” Suubi broke the sad news. Uncle Nkalyanzekka took in the news, without much of an expression. “Come in,” he finally allowed him in.” Suubi gingerly stepped on to the carpet.

“But I hear those people were supporting guerrillas,” his Uncle snapped, after taking in all the news. “So, what can I do for you!” He started pressing him.

“I need somewhere to stay,” Suubi pleaded.

“We have only a small place here,” the Uncle, who had two children, mostly away in a boarding school, wavered. It was only when his wife later showed up and hearing Suubi’s story of what had happened in the village urged her reluctant husband to take his nephew in. “He can also help us with chores, anyway.”

This is how Suubi had ended up being raised as a Shamba boy in his Uncle’s palatial home. He was housed in a boy’s quarter. Life was restless as the deal was to do odd jobs around the house as a way to earn money to pay for his school fees. Through hard work Suubi had finally made it to the university, and soon got a job in a government agency. Finally secure, he felt it was now time to live the life of his dreams, just like his pinchy Uncle.

But then he was in for a rude shock. Soon after leaving university Suubi saw one of his best friend die of a mysterious disease that had drained him into a poor skeletal frame. By then there were people dying all over, taken by a new strange disease. Finally someone gave it a name- Slim. After a lot of research, it was discovered, it was largely caused through sexual activity with an infected person. Young people like Suubi were urged to marry and stick to their partners, if they were ever to avoid it.

So, when Suubi married a girl called Mary, he knew his troubles were over. After all he had now a good job, a wife, a house and soon a car, all to himself. He would now be like Uncle Nkalyanzekka, a wealthy man living in the city, enjoying life to himself.

One of the things that had drawn Suubi to Mary was that she had grown up in a hard up family, far away from the village, much like his. But Suubi and Mary had hardly settled in their new life of tranquility when in quick succession she lost four of her elder brothers to Slim. Her parents back in the village decided to send two of her remaining sisters, still in school, to her to raise. “With our grief, we can only manage to look after one child.”

Suubi’s first reaction was to send them back. “Why are your people coming here to enter our quiet life!” he wondered aloud. Mary did not answer. But later, as he reflected back on his life, Suubi recalled he had survived because someone had let him in, albeit reluctantly. Otherwise he would have ended up on the streets. Maybe by letting in these two girls, they too would survive, just as he had scrapped through the bush war, and go on to become something.

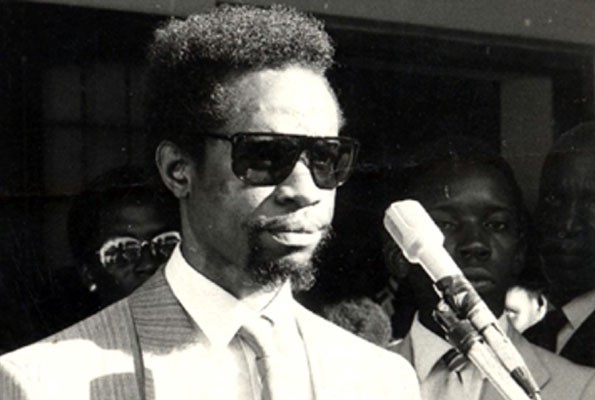

Those are the stories of Slim days. Although looked at as a very wicked period, and certainly it was, there is also a lot of good that came out of that dark period. In 1988 at its worst, a musician by the names of Phily Lutaaya, gave a feared disease a human face, by boldly presenting himself, and going a long way to reduce the stigma that had left many to suffer in morbid silence.

Earlier in 1987 after losing her husband to HIV/ AIDS, a young widow called Noreen Kaleeba, decided to turn a tragedy into an opportunity, by linking up with others who had experienced as much fate, with a simple mission, to lift up each other and find a way for life to go on. Eventually, from this band of widows, would grow one of the most respected global health organization called TASO, which has gone a long way to end this disease.

Times of tragedy can also birth the most heroic feats, as the days of HIV/AIDS revealed. On the other hand there are those who can become withdrawn and perhaps callous. Throughout history even in dark times, often in the midst of falling bodies, there are those who see this as their best opportunity to collect sacks of money they always longed for and build mountains of castles for their enjoyment. That’s how life goes.

But still, there are those who choose to rise above the waters, forget about themselves, even if for a while, and become bigger, as we saw back then.

The Covid- 19 pandemic is no less, of times of upheaval seen through history. In spite of all the misery, it is a gift as well, to mankind, because it helps us draw back to find the very essence and meaning of life. At the end of it some will come out narrower in life; as other will have risen to become larger in life.

Surely , out of diversity emerges an opportunity. Much as this would have been a time to improve the country’s health system, to some its a cash bonanza.